Tourbe Chunky, 2021

Guillaume Adjutor Provost

in conversation with

Toshio Matsumoto

TRUCK Contemporary Art, Calgary (Canada)

October 29 - December 11, 2021

In the form of assemblages, the recent works of Guillaume Adjutor Provost are reunited in the exhibition Tourbe Chunky, examining the proximity between the occidental history of economics and its multiple references to the human body. The works were initiated during a research and creation residency at Lieu Unique in Nantes (France) in the fall of 2019, and completed just before the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

According to essayist Éloi Laurent, recent developments in the discipline of economics, which celebrate efficiency at the expense of equity, have fostered the uncontrolled development of social inequalities. Passed in silence, these inequalities push individuals and groups to evolve gradually in separate — even impervious — social universes where information, events and realities have neither the same meaning nor the same value. Following Laurent's thinking, the three hopes of humanity in the 21st century (well-being, resilience and sustainability) are blinded by the concept of growth and almost completely escape our current systems of economic measurement and management. It is interesting to go to the roots of the term "growth" since it emerges in reference to the human body and health. On this subject, the exhibition draws on the work of the physiocrat and physician François Quesnay (1694-1774), theorist of the Tableau économique (1758). From its medical standpoint, Quesnay’s work led to comparing commerce with blood circulation and social class with vital organs.

How does this circulation between the social organs really take place? Could we imagine a human body in which only the stomach would grow at the expense of all the other organs, invading their space and ending up using them as food? It is here that the mythology of economics as medicine of the social body, inherited from neoclassical thought, is called into question.

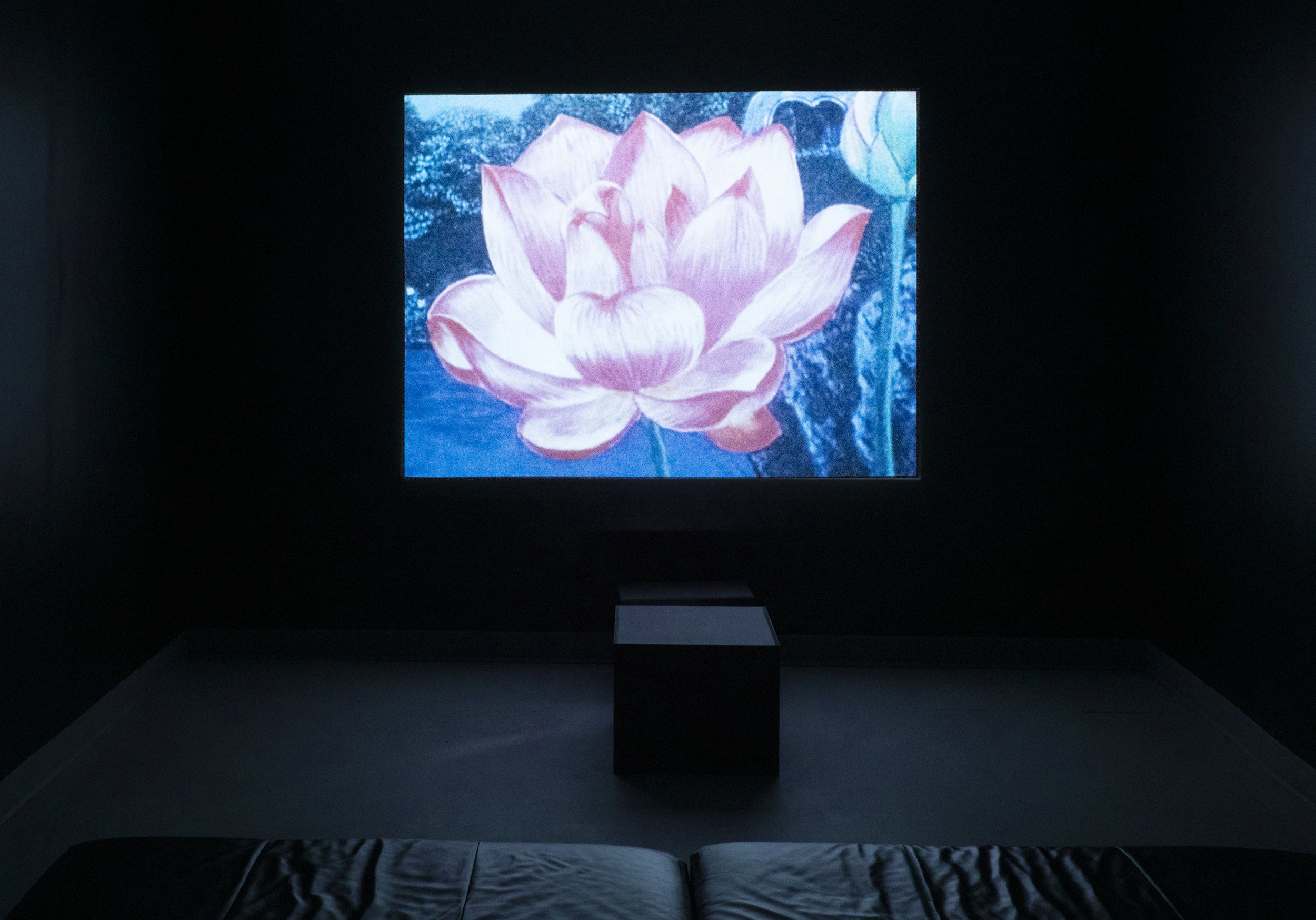

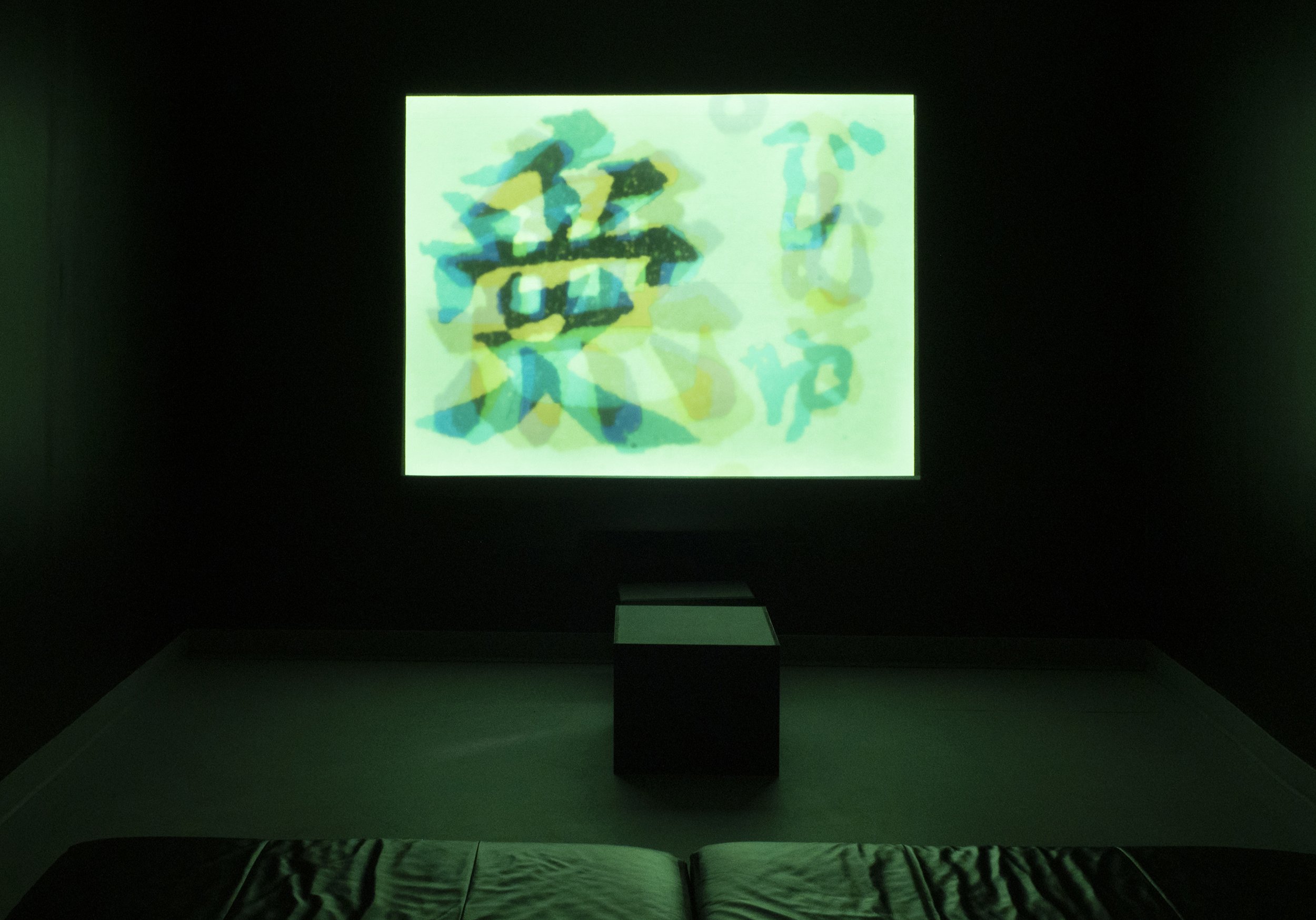

The transformations of economic thought at the turn of the 19th century are suggested by a body from which the skeleton has been extracted. These skeletons, which here symbolise philosophical and ethical considerations neglected in favor of growth, punctuate several works in the installation. Textiles are added to some works which are used to cleanse the body: towels, handkerchiefs, table linens. The suspended cork sculpture is reminiscent of a tongue covered with pieces of lead. On the ground, puddles of fake vomit echo what is being rejected, often violently, by the system / body. Finally, in the viewing room, the flagship work Everything is Empty (1975) by Japanese post-war videographer Toshio Matsumoto is shown on a loop. Stroboscopic and generous, the video work has been curated in order to bridge the gap with other works that can be emotionally demanding.

Guillaume Adjutor Provost would like to thank the TRUCK Contemporary Art team : Alicia Buates McKenzie / Nura Ali / Alberta Rose, Laurence Dubuc, and Rémi Martel.

This project was made possible with the support of Canada Council of the Arts, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, the Postwar Japan Moving Image Archive, and le Lieu Unique

Photo Credits : Elyse Bouvier

Artworks

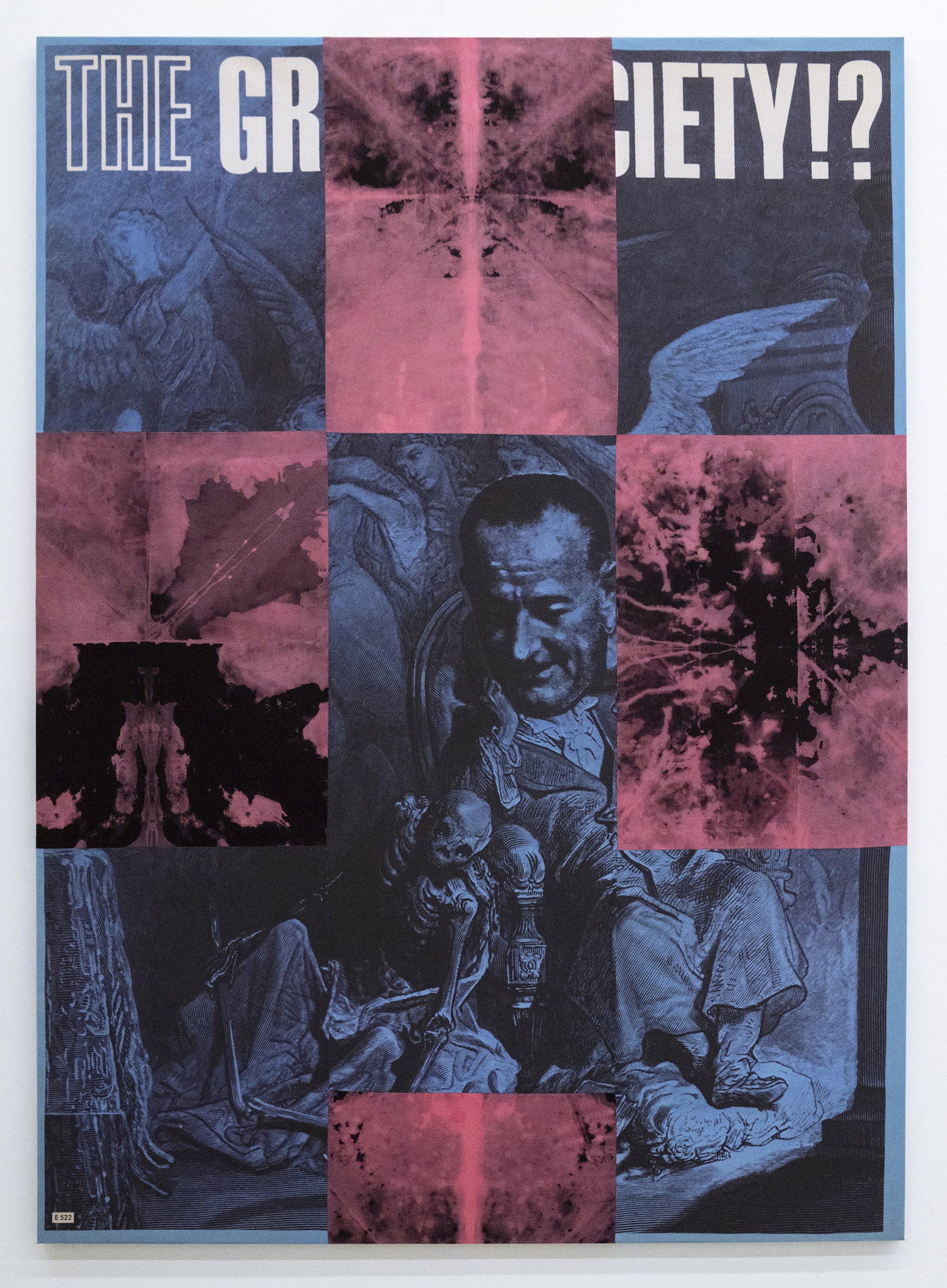

The Great Society!?, 2020

Overdye and digital print on fabric

185 cm x 132 cm

The background of The Great Society!? comes from a typical psychedelic poster from the International Poster Corp collective. (1968) opposing President Lyndon Johnson and the Vietnam War. We see Johnson sitting in an armchair, looking at a skeleton, angels by his side. At the time, the collective used Gustave Doré's original illustration from the 1884 edition of The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

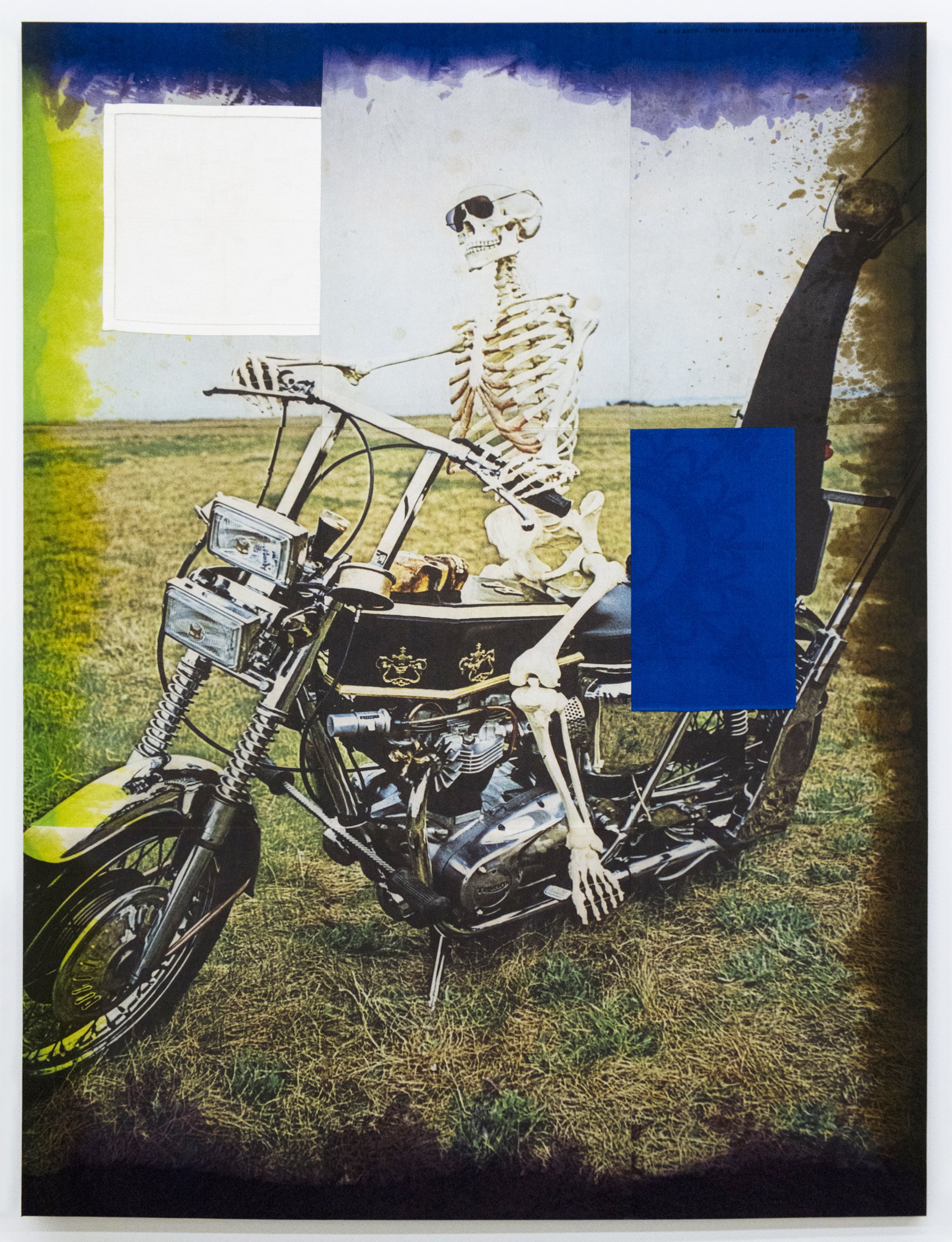

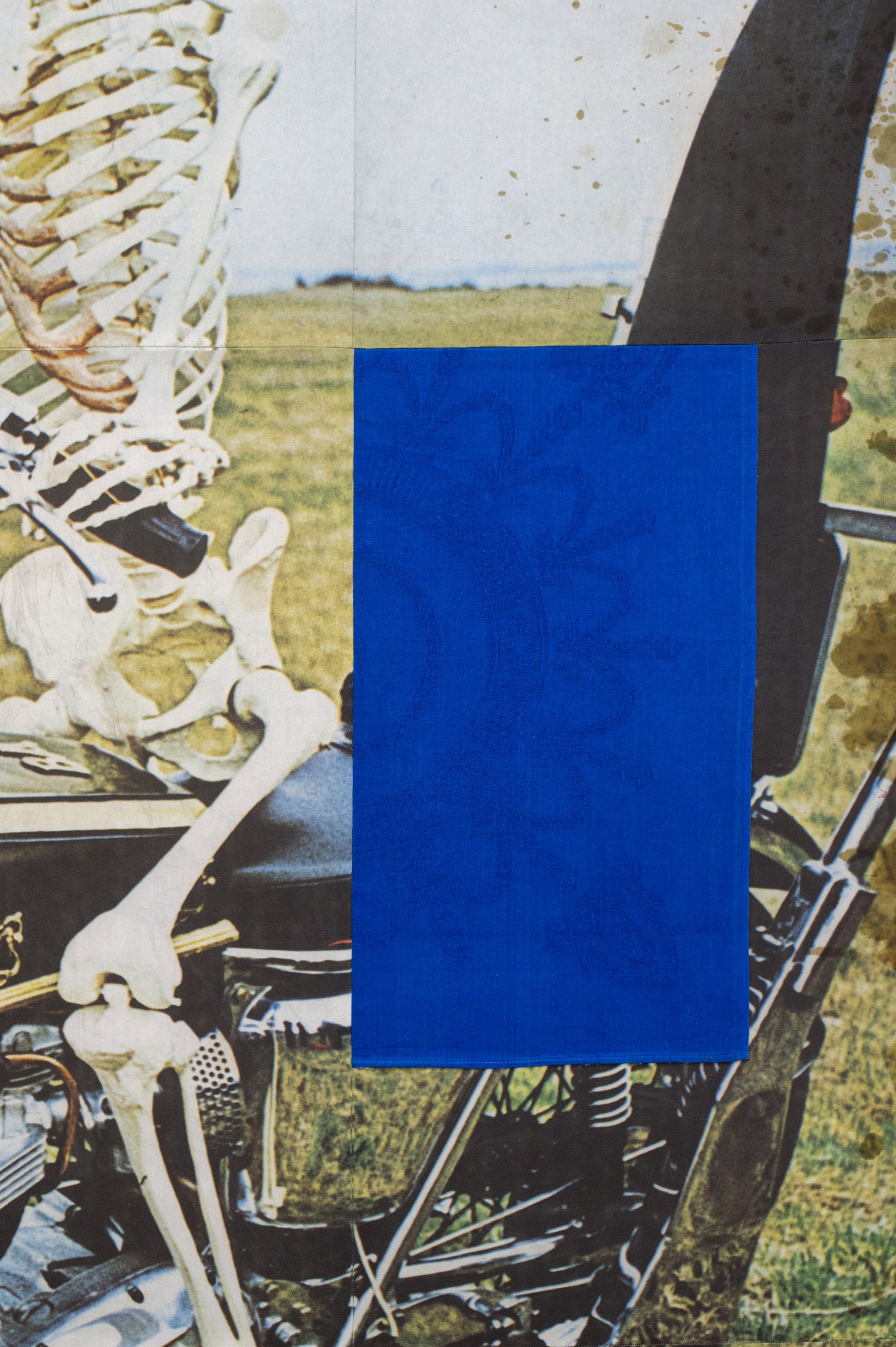

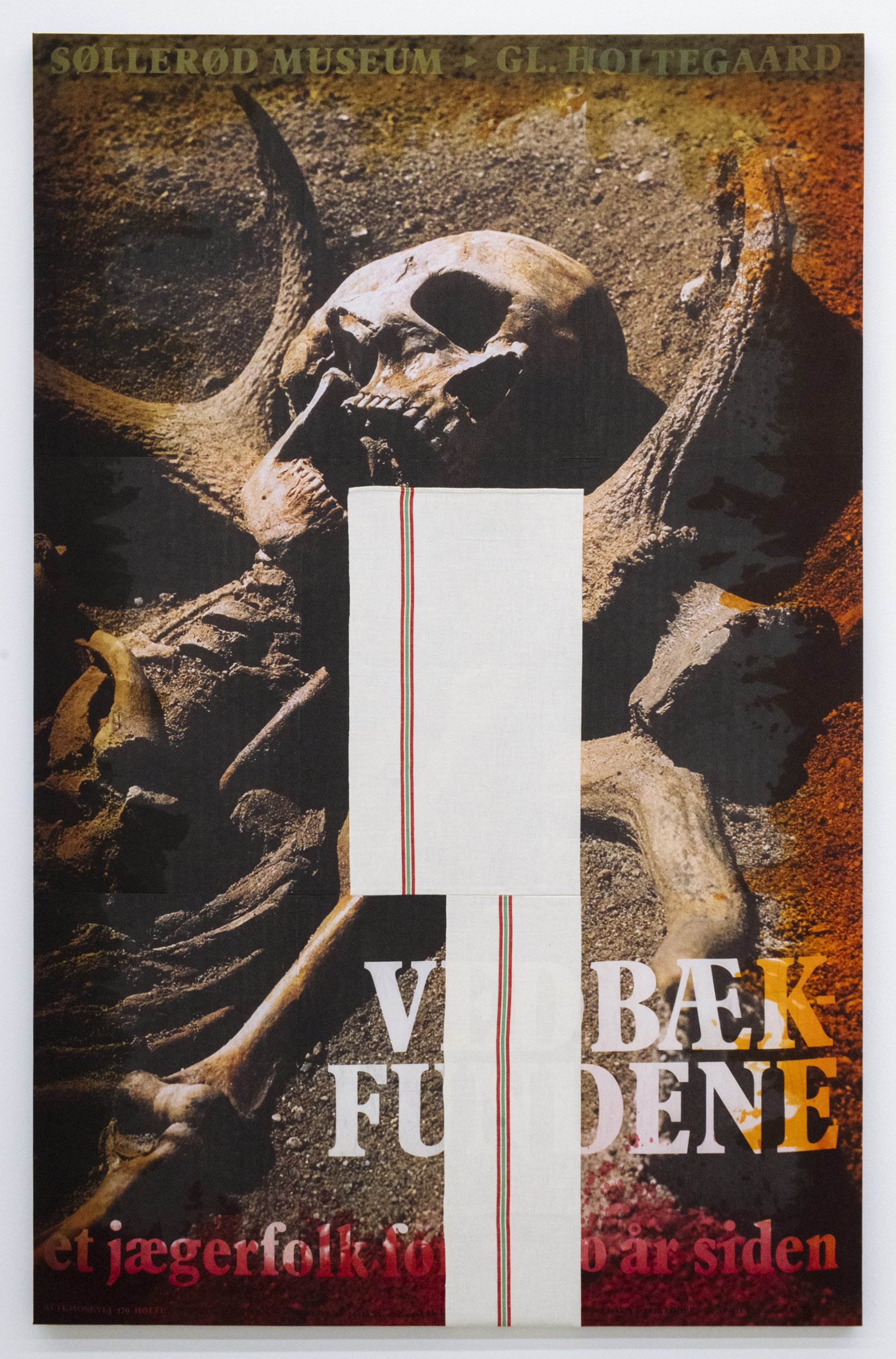

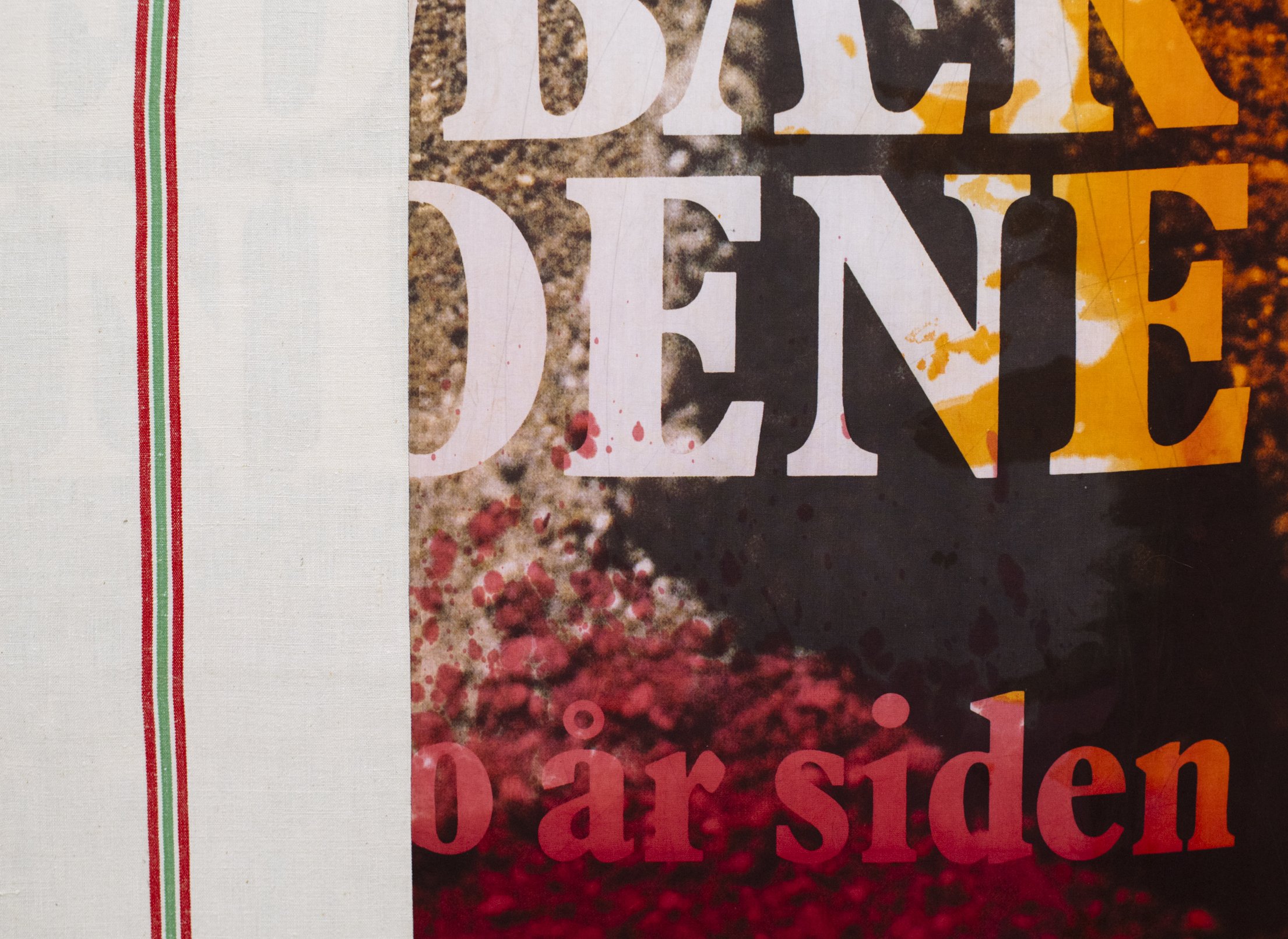

Happy Skeleton Riding a Motorcycle [Philosophy], 2020

Overdye and digital print on fabric

185 cm x 132 cm

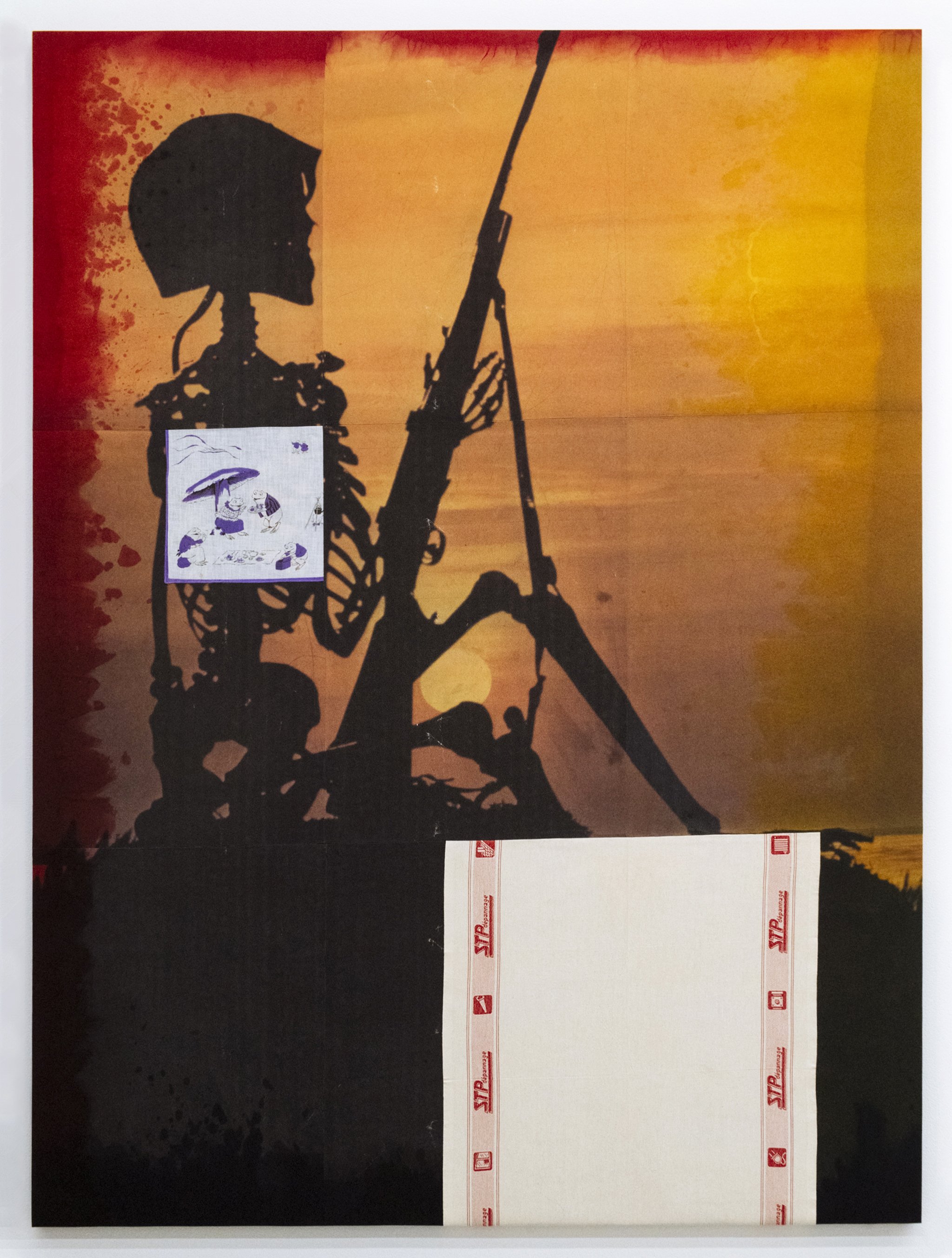

The posters from which Melancholic Skeleton Looking at the Horizon [Philosophy] and Happy Skeleton Riding a Motorcycle [Philosophy] are built were produced in the mid-1970s in Denmark by the Wagner Graphics company. These images were intended to be distributed at carnivals or sold in record stores. Their distinctive, albeit generic, imagery evokes a Rock n 'Roll attitude or even a reflection on the Second Indochina War. The works are recomposed from sections dyed independently and on which are glued textile pieces used to clean or dry the body: table linens, napkins, handkerchiefs.

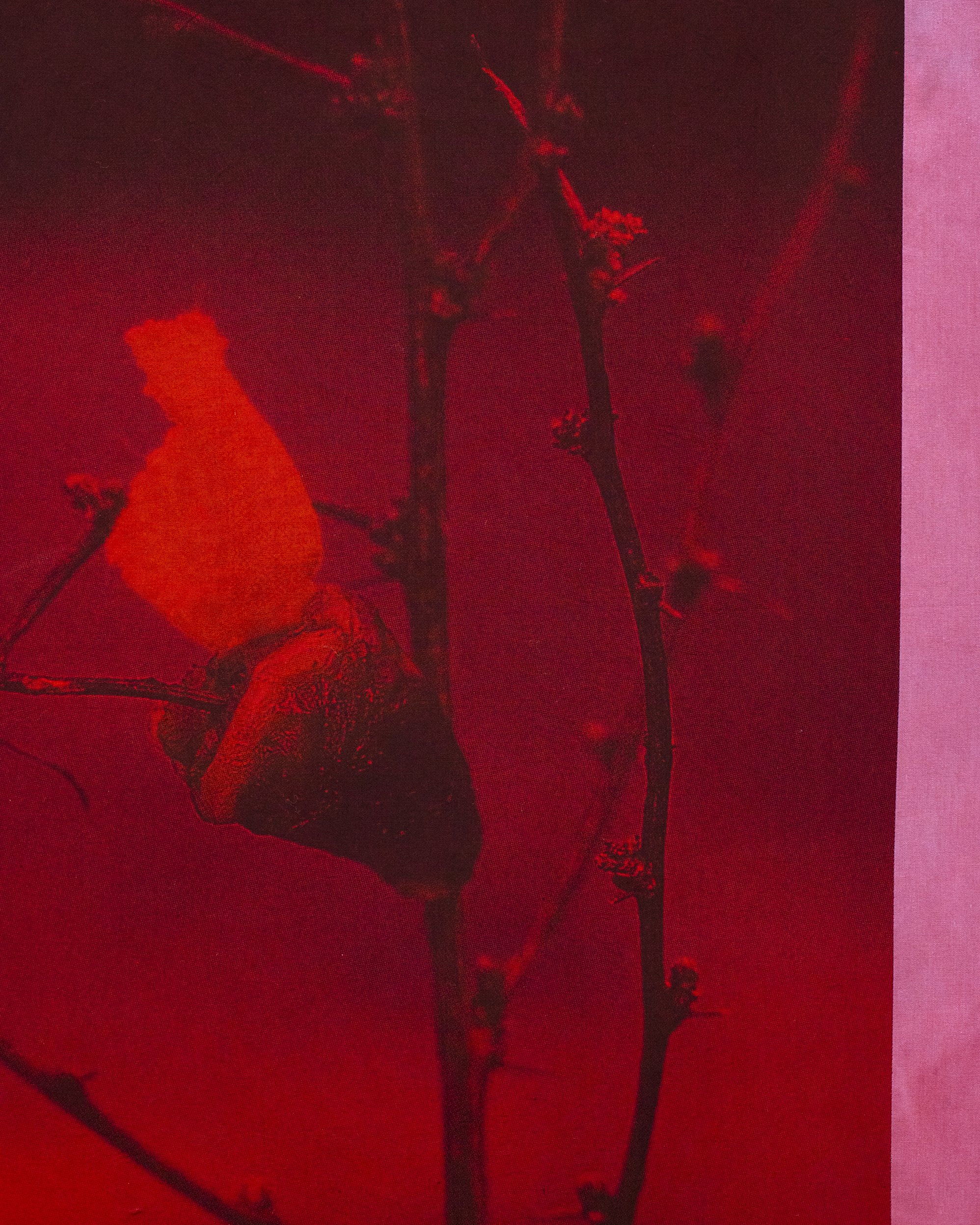

Red Foxgloves with Thorns [Neoliberalism] V.2, 2020

Overdye and digital print on fabric

147 cm x 81 cm

Foxglove is an extremely toxic plant from which digitalis is extracted, used as a cardiac tonic. Given its toxicity, the use of this plant is unpredictable in herbal medicine, but occupies an important place in the witchcraft ideation. Considering that the world is an organized totality comprising two faces in constant interaction: esoteric and exoteric; Foxglove is the symbol of the heart, a poison as well as a remedy.

Melancholic Skeleton Looking at the Horizon [Philosophy], 2020

Overdye and digital print on fabric

178 cm x 132 cm

Primate, 2020

Overdye and digital print on fabric

196 cm x 119 cm

Rooster Heart with Thorns [Patriarchy], 2020

Overdye and digital print on fabric

134 cm x 81 cm

The tool, called "load", constitutes a space of projection and influence linked to a person, thing, place or concept. The process is widely documented in witchcraft practices in central Europe. Connected with Baudrillard's thought, the simulacrum allows the attention of symbolism to be shifted towards "a real without origin or reality: hyperreal".

Blurring Big Tongue, 2019

Cork bark, lead, x-rays, steel cables

350 cm x 44 cm x 35 cm

Cioran Slapstick [vomit], 2020

Urethane resin, expired dry goods given by neighbours, pocket money

Edition of 7 variables

Ranging from 45 x 48 cm to 27 x 25 cm

Projection room

Toshio Matsumoto

Everything Visible Is Empty [Siki Soku Ze Ku], 1975

16 mm transfered to video

colour, sound by Toshi Ichiyanagi

4:3, 7m45s

------------------------------------------------------------------

Guillaume Adjutor Provost / TOURBE CHUNKY

Text by Anaïs Castro

The artistic practice of Guillaume Adjutor Provost is informed by his wide range of interests: sociology, economics and philosophy, but also botany and literature. In his work, these different fields of knowledge exist concurrently within images and objects carefully placed in the gallery. The artist transforms the exhibition space into an arena of experimentation in which concepts can be reimagined, reconfigured and challenged through the process of free associations.

For this solo exhibition titled Tourbe Chunky at TRUCK, Provost departs from an idea drawn from Tableau économique, a text written in 1758 by the French physician and proto-economist François Quesnay. Joining two fields of work, medicine and economic theory, his work draws a loose analogy between commerce and blood circulation and between social class and vital organs. This connection between capital and body is firmly inscribed within economic linguistics, yet it eludes common knowledge. It’s in Benjamin Franklin’s famous citation: “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.”

Compelled by the economic myth of a malfunctioning body-society, Provost initiated this new body of work during a residency at Lieu Unique in Nantes, just before the COVID-19 pandemic. Provost could not have predicted then how global circumstances would come to inform this production. Whether it is through Blurring Big Tongue, a garland of x-rays and bark that dangle from the ceiling like an uvula, through the repetitive use of the skeleton as a motif in most of the printed fabric wall pieces: Rooster Heart with Thorns [Patricharchy], Melancholic Skeleton Looking at the Horizon [Philosophy] , The Great Society!? and Happy Skeleton Riding a Motorcycle [Philosophy] or via the series of Slapstick sculptures that occupy the gallery floor as retch puddles, the body is unilaterally presented in Provost’s work as an ailing system.

The artist is undoubtedly aware of the wide semiology associated with the body. His use of skulls, for example, recalls the historical representation of vanitas connoting the transient nature of human life and the certainty of death. But more than that, this also marks an association to philosophy and critical thought. His material choices and visual glossary often compel the viewer to see beyond the mere surface. In this way, Provost’s work is also deeply informed by Jean Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality, that is to say when simulacra and symbols blend in with their referent to a point of complete interchangeability or when signifiers stand independently as their own signified. Within a neoliberal, post-truth society it often appears as if the Hyperreal has come to fully replace the Real.

Guillaume Adjutor Provost’s work is the product of a boundless indexical society. The artist collects images, recording their provenance and researching the contemporary and historical relevance of their subject matter before reconfiguring them within a renewed context. Ultimately, Guillaume Adjutor Provost’s artistic gesture is often one of displacement. He drags images out of their context while tracing the line of this gesture towards connecting fields of research and knowledge. Giorgio Agamben defined the condition of the contemporary as adopting a dissonant posture. This is an adept perspective from which to consider Adjutor Provost’s practice, for the action of displacement invariably implies two opposing movements: a landing, but also a rupture. It is precisely in this dual operation that the compelling potential of Provost’s practice is situated. It reminds us that to exist within Capitalism is to live among contradictions.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Tourbe Chunky, 2021

Guillaume Adjutor Provost

En conversation avec

Toshio Matsumoto

TRUCK Contemporary Art, Calgary (Canada)

29 octobre - 11 décembre 2021

Sous forme d’assemblages, les œuvres récentes de Guillaume Adjutor Provost rassemblées dans l’exposition Tourbe Chunky examinent la proximité entre l’histoire de l’économie et ses références multiples au corps humain. Les œuvres ont été initiées lors d’une résidence de recherche et de création au Lieu Unique à Nantes (France) à l’automne 2019, puis complétées tout juste avant la pandémie de COVID-19.

Selon l’essayiste Éloi Laurent, les développements récents de la discipline économique, célébrant l’efficacité au détriment de l’équité, a favorisé le développement incontrôlé des inégalités sociales. Passées sous silence, ces inégalités poussent les individus et les groupes à évoluer progressivement dans des univers sociaux séparés, voire étanches, où les informations, les événements et les réalités n’ont ni la même signification, ni la même valeur. En suivant la pensée de Laurent, les trois espoirs de l’humanité au XXIe siècle que sont le bien-être, la résilience et la soutenabilité échappent à peu près complètement à nos systèmes actuels de mesure et de pilotage économiques, aveuglés par le concept de croissance. Il est intéressant de retourner à la racine du terme « croissance » puisque celui-ci émerge en référence au corps humain et à la santé. À ce sujet, l’exposition puise dans l’œuvre du physiocrate et médecin François Quesnay (1694-1774), théoricien du Tableau économique (1758). Issue d’une pensée d’abord médicale, l’œuvre de Quesnay menait à comparer le commerce à la circulation sanguine et les classes sociales aux organes vitaux.

Comment s’opère réellement cette circulation entre les organes sociaux? Imaginerait-on un corps humain dans lequel seul l’estomac croitrait au détriment de tous les autres organes, envahissant leur espace et finissant par les utiliser comme aliments? C’est ici la mythologie de l’économie comme médecine du corps social, héritée de la pensée néo-classique qui est remise en question.

Les transformations de la pensée économique au tournant du XIXe siècle sont suggérés par un corps dont on aurait extrait le squelette. Ces squelettes, qui symbolisent ici les considérations philosophiques et éthiques délaissées au profit de la croissance, ponctuent plusieurs œuvres de l’installation. Sur certaines œuvres sont ajoutés des textiles qui servent à nettoyer le corps : serviettes, mouchoirs, linges de table. La sculpture en liège suspendue rappel une langue couverte de pièces de plomb. Au sol, des flaques de vomit factices font échos à ce qui est rejeté, de manière souvent violente, par le système/corps. Enfin, dans la salle de visionnement est projetée en boucle l’œuvre phare Everything is Empty (1975) du vidéaste de l’après-guerre nippon Toshio Matsumoto. Stroboscopique et généreuse, l’œuvre vidéo a été commissariée afin de faire un pont avec les autres œuvres qui peuvent s’avérer émotionnellement exigeantes.

Guillaume Adjutor Provost aimerait remercier l’équipe de TRUCK Contemporary Art : Alicia Buates McKenzie / Nura Ali / Alberta Rose, Laurence Dubuc, ainsi que Rémi Martel.

Ce projet a été rendu possible grâce au soutien de Canada Council of the Arts, the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec, the Postwar Japan Moving Image Archive et le Lieu Unique

Crédits photo : Elyse Bouvier

Œuvres exposées

The Great Society!?, 2020

Surteinture et impression numérique sur textile

185 cm x 132 cm

L’arrière-plan de The Great Society!? provient d’une affiche psychédélique typique du collectif International Poster Corp. (1968) s’opposant au président Lyndon Johnson et la Guerre du Vietnam. On y voit Johnson assis dans un fauteuil, regardant un squelette, des anges à ses côtés. À l’époque, le collectif avait utilisé l’illustration originale de Gustave Doré, tirée de l’édition de 1884 de The Raven d’Edgar Allan Poe.

Happy Skeleton Riding a Motorcycle [Philosophy], 2020

Surteinture et impression numérique sur textile

185 cm x 132 cm

Les affiches desquelles sont construits Melancholic Skeleton Looking at the Horizon [Philosophy] et Happy Skeleton Riding a Motorcycle [Philosophy] ont été produites au milieu des années 1970 au Danemark par la compagnie Wagner Graphics. Ces images étaient destinées à être distribuées dans des carnavals ou vendues dans des magasins de disques. Leur imagerie typée quoique générique évoque une attitude Rock n’ Roll ou encore une réflexion sur la deuxième guerre d’Indochine. Les œuvres sont recomposées à partir de sections teintes indépendamment et sur lesquelles sont collés des pièces textiles servant à nettoyer ou sécher le corps : linges de table, serviettes, mouchoirs.

Red Foxgloves with Thorns [Neoliberalism] V.2, 2020

Surteinture et impression numérique sur textile

147 cm x 81 cm

La grande digitale est une plante extrêmement toxique dont on extrait la digitaline, utilisée comme tonicardiaque. Compte tenu de sa toxicité, l’usage de cette plante s’avère imprévisible en phytothérapie, mais occupe une place importante dans l’imaginaire sorcier. Considérant que le monde est une totalité organisée comprenant deux faces en constante interaction : ésotérique et exotérique; la grande digitale est le symbole du cœur, un poison autant qu’un remède.

Melancholic Skeleton Looking at the Horizon [Philosophy], 2020

Surteinture et impression numérique sur textile

178 cm x 132 cm

Primate, 2020

Surteinture et impression numérique sur textile

196 cm x 119 cm

Rooster Heart with Thorns [Patriarchy], 2020

Surteinture et impression numérique sur textile

134 cm x 81 cm

L’outil, nommé « charge », constitue un espace de projection et d’influence lié à une personne, une chose, un lieu ou un concept. Le procédé est largement documenté dans les pratiques sorcières de l’Europe centrale. Mis en relation avec la pensée de Baudrillard, le simulacre permet de décentrer l’attention du symbolisme vers « un réel sans origine ni réalité : hyperréel ».

Blurring Big Tongue, 2019

Écorce de liège, plomb, rayons X, câbles en acier

350 cm x 44 cm x 35 cm

Cioran Slapstick [vomit], 2020

Résine uréthane, nourriture périmée donnée par les voisins, argent de poche

Édition de 7 variables

Dimension entre 45 cm x 48 cm et 27 cm x 25 cm

Salle de projection

Toshio Matsumoto

Everything Visible Is Empty [Siki Soku Ze Ku], 1975

16 mm numérisé

Couleur, trame sonore par Toshi Ichiyanagi

4:3, 7m45s